BIO

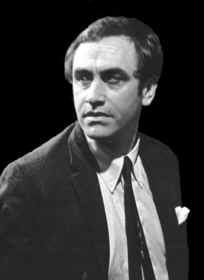

He was six foot four inches tall, with broad shoulders, dark brown hair, brown eyes, and strong, almost-handsome features. His reedy mid-range voice cracked when he shouted, and he spoke with a muted, rather generic British accent and a rapid, clipped, dry delivery that lent itself to glibness and innuendo. A gifted silent actor, very much “in his body,” with a mobile, expressive face and an uninhibited ease of gesture, he excelled at projecting humor and dangerousness. He appeared mostly in comedies and action films, often as a villain or morally ambiguous “charming rogue” type.

Childhood

James Booth came into the world as David Noel Geeves on 12/19/27 in Croydon, Surrey, England. His father, Ernest Edward Geeves, and his mother, Lillian Alice (nee Edwards), were both second-generation Salvation Army officers and met in that organization. Young David and his only sibling, a sister Jackie eight years his junior, had a highly religious upbringing. They went to church “three times on Sunday and three times during the week” and heard endless lectures from Ernest on the evils of drink. The Geeves family relocated frequently, as their ministerial duties demanded, but always lived in working class areas, where Ernest’s white-collar income as a probation officer made them better off than their neighbors. Reportedly jovial and generous almost to a fault, Ernest brought home a steady stream of unfortunates and instilled in David a permanent sympathy with the underclass. Ernest was disabled during WWI, with a recurring partial paralysis that left him at times unable to walk. He died of his wounds in 1938, when David was eleven. (During David's teenage years, Lillian married her second husband, Clifton Barnes, also an officer in the Salvation Army.)

David attended Southend Grammar School, where he was, he said, an indifferent student and a bit of a rebel. “If I couldn’t be first, I wasn’t going to be second, so I opted out.” His rebellious attitude extended to the subject of alcohol. Reacting against his father's admonitions, young David resolved, "As soon as I'm old enough I'll get as drunk as I can. "

The “Wilderness Years”

After leaving school at age 17, Geeves was drafted into the army and served for three years (or five years--the sources differ). At one point he was tasked with training recruits in the use of the bayonet, but eventually he rose to the rank of captain in tank transport.

He was stationed at Bury St. Edmonds, Aldershot, and Cirencester. Though he saw combat only “from afar,” one lasting effect of Geeves’s military service was minor hearing damage.

Discovering Theater

Deciding the army was “no fun anymore,” Geeves returned to civilian life. He studied business for a year at Municipal College in Southend-on-Sea, Essex, and then found new employment with the London office of a diamond mining company. On the side, he began acting in Southend’s amateur theater, including productions of Romeo and Juliet and The Beggars' Opera. Geeves so impressed the director that at his urging Geeves applied for and received an L.L.C. scholarship to the Royal Academy of Dramatic Art (RADA).

Despite opposition from his mother and step-dad, who were "horrified" by his thespian ambitions, Geeves attended RADA for two years, from 1954 to 1956. His classmates included Albert Finny, Peter O’Toole, Alan Bates, and many others who were to become famous. The atmosphere was intensely competitive. Geeves had hated competition in grammar school and he hated it now. He described his experience at RADA as “horrible.” Nevertheless RADA gave David Geeves at least one important professional connection--Producer Irving Allen, who would eventually sign him to an exclusive movie contract and help him out in other ways over the years.

While enrolled at RADA, Geeves also met the love of his life. Geeves had been hired to act in a professional stage production at the New Lindsay Theatre in Notting Hill Gate. "They wanted someone to play a gangster role," he told Preview Film Album. "I was always a cinch for a part like that!" The stage manager was Paula Delaney, a tall brunette with (as David later put it) "a sense of humor." Though they barely noticed each other at first, over the course of the next three years, David and Paula fell in love. They married in 1960 and the union lasted until his death.

James and

Paula at the premier of Zulu.

James and

Paula at the premier of Zulu.

The early years of the marriage were somewhat difficult because Paula earned more as a stage manager than David did as an actor. In addition, Paula took care of the house. But Paula's faith in her husband, which David described as “tremendous,” gave him a “very deep sense of security” for the first time in his life. Without the “anchor” provided by Paula and their four kids, he said “I probably would have drunk myself to death….Paula saved me.”

James and the four kids (left-to-right): Matthew,

Charlotte, Sarah, and Jason

James and the four kids (left-to-right): Matthew,

Charlotte, Sarah, and Jason

At some point during the early stages of his career, David Geeves was told to change his name because “it sounded too much like a butler.” He adopted the last name of Booth, in honor of Salvation Army founder William Booth. But the name David Booth was already registered with Equity. So David adopted his grandfather’s first name and became James Booth (or, informally, "Jimmy").

Theatre Workshop

After “carrying a spear” at the Old Vic for two years, 1956-57, Booth took an important step forward in 1958 when he joined the Theatre Workshop, an experimental theater group led by the brilliant, but abrasive and eccentric, Joan Littlewood. An avowed communist, Littlewood recruited untrained actors off the streets and gave her Workshop the tagline “A British People’s Theatre.” She called her company “my nuts” because they put up with craziness like learning a whole play without knowing which actors would be playing which roles. Improvisation was a big part of Workshop method. Booth’s inventiveness and sense of humor quickly made him one of Littlewood’s favorites.

Booth had his first taste of real success in a Workshop musical about the London underworld called Fings Aint Wot They Used T’Be, which became a hit and ran from 1959 till 1962. In fact, Booth deserves some credit for discovering Fings in the first place. The manuscript had sat on Littlewood’s desk unread until Booth “breezed in” and took an immediate interest in it because he knew and admired its author, the ex-con Frank Norman, from his previous work, the prison memoir Bang to Rights. Booth took Fings home to read and returned to Littlewood’s office with composer Lionel Bart, who thought Fings would make a good musical. Bart called Fings “[the] first time I’ve heard cockney written as she is spoke.” The show was set in a tavern and dealt with criminals, prostitutes, and ne’er-do-wells. Other notable members of the cast included George Sewell, Roy Kinnear, and Barbara Windsor, all of whom would appear with Booth in films later on. Windsor recalls, "I was completely bowled over by Jimmy Booth" and says they had "a little affair" at that time.

Many people were bowled over by Booth in Fings. His character, Tosher the pimp, had originally been conceived as "an old geezer"; Booth turned him into someone “young and lively,” as Littlewood put it. His performance and his song, “The Student Ponce,” came in for special praise from the critics. Booth fit the role perfectly—possibly because he may have been playing himself to some extent. “Tosher was me,” Booth has admitted.

A Shot at the Big Time

Before Fings, Booth had been a struggling actor like any other, lucky to

get tiny bit parts in The Narrowing Circle (1956) and The Girl in the

Picture (1957). Now Booth was a hot property. Producer Irving Allen,

pro-Booth since their first meeting in Booth's RADA days, signed Booth to a hundred-thousand

pound contract with Warwick Films and gave him leading roles in Jazz Boat

(1959), In the Nick , (1960), and

The Hellions (1961).

Booth later admitted he hadn't cared much for the films themselves, but remained

grateful for the exposure they gave him, which helped cause a Booth mini-vogue. Suddenly

Booth was everywhere. Between 1960 and 1965 he appeared in eleven films,

once making four in a single year. All this attention earned Booth a listing in

Who’s Who, where he said he enjoyed underwater fishing and his favorite

roles were those in which he could relax. Ken Ferguson, in

Photoplay,

wrote, "Watch this man...I predict he will be a star."

Unfortunately, although this period generated most of Booth's best work

(including Joan Littlewood’s only film,

Sparrows Can’t Sing [1963];

Kurt Russell’s first film, French

Dressing [1964]; and Jiri Weiss’s arty

Ninety Degrees in the Shade

[1965]), little of this material remains in print. The chief exception is

Zulu (1964), a frequently-televised

classic in which Booth gives his best-loved and best-remembered performance ever as the

reluctant war hero Pte. Henry Hook, aka “Hookie.”

James Booth, as Hookie, stealing the after-battle roll-call scene

at the end of Zulu

James Booth, as Hookie, stealing the after-battle roll-call scene

at the end of Zulu

This was success of a kind, but Booth remained dissatisfied. He felt typecast. With a few exceptions the characters he played were Cockney rogues and criminals. Booth individualized them as much as he could, but he increasingly regarded humorous Cockney material as a strait-jacket. Determined to broaden his range, Booth said no to some valuable opportunities (he turned down the lead role in Alfie, for instance) and yes to some questionable projects. He also began distancing himself from the Tosher character, protesting in interviews that his public image was wrong--he wasn't a shady layabout, or a 24/7 drink-till-you-drop party-animal. Not any more. He worked hard all day and then went home to his wife and kids.

However admirable Booth's attempt to reposition and stretch himself professionally, it yielded few concrete rewards. Its main effects were to blur Booth’s identity as an actor and to create confusion about the kinds of roles he was seeking.

Disaster

James Booth as Robin

Hood in Twang!!

James Booth as Robin

Hood in Twang!!

The first serious blow to Booth’s career came in 1965 in the form of a musical about Robin Hood called Twang!! On the surface, Twang!! looked promising. It would bring together Joan Littlewood, Lionel Bart, Frank Norman, and a cast that included the Theatre Workshop’s strongest players. It also had the potential to be a great vehicle for James Booth, who was repeatedly told he was the only person who could do justice to the Robin Hood role, and who was repeatedly assured that the small part would be expanded to starring dimensions.

Unfortunately, on a deeper level Twang!! was a disaster from the word go. The script was weak and stayed that way, especially the part of Robin Hood, despite constant, confusing rewrites. Rehearsals were disorganized. In front of the whole company, Littlewood accused Bart of being too strung-out on LSD to fulfill his creative responsibilities. A “theater doctor” was brought in to salvage things, leading to still more confusing changes, but nothing helped. The show opened in disarray and closed soon after, to universal scorn and derision. Bart had invested his personal fortune in Twang!!. He lost everything.

James Booth had never felt good about Twang!!. Against his own better judgment he had allowed himself to be flattered and cajoled into accepting the half-baked part of Robin Hood when he could have been doing other things. He had voiced his concerns over and over again, sticking with Twang!! only from a sense of obligation. He had made no money during the year it took to prepare for Twang!!. By February, 1966, Booth was unemployed and tainted by the stigma of Twang!!’s failure. He had two mortgages on his house and owed taxes. As if all that weren’t enough, a storm destroyed his roof and Booth began to suffer from a vitamin deficiency and other health problems.

Second Chance

Four months later, in July, fortune finally smiled on Booth and he was saved again, this time by Hookie. Joseph E. Levine and Harold Robbins had reportedly seen Zulu and liked Booth’s performance so much that on its strength alone Levine signed Booth to a three-year contract. Robbins set Booth and family up in the villa next to his own at Cannes for six weeks. Booth emerged from this vacation in improved health. The following year, he made the true-crime thriller Robbery (1967) and accepted a starring role in the marital comedy The Bliss of Mrs. Blossom (1968).

Neither of these films (nor the well-regarded Fräulein Doktor [1969], much less the creepy western Macho Callahan [1970]) was the breakthrough vehicle Booth’s career needed. Had he been able somehow to exploit or duplicate the appeal of the ever-popular Hookie characterization (for example, by turning the Flashman books into a TV series or film franchise--Flashman is a similar character, as many people have observed), Booth might have carved out his own unique niche and become one of those everlasting entertainment fixtures. But no such opportunity came his way. Booth was later to opine that signing that contract had been a mistake: “I wasn’t allowed to make any films.” Certainly he wasn’t allowed to make any films that would meaningfully advance his career.

Instead, Booth appeared in such undistinguished potboilers as the low-budget but oddly enjoyable kitsch thriller Revenge (1971) and the widely-panned comedy Rentadick (1972). In addition, Booth appeared in some interesting-sounding television shows. The Vessel of Wrath (1970), based on a story by the same title by W. Somerset Maugham, gave Booth a perfect vehicle in the character of Ginger Ted, a womanizing drunkard who finds true love with a prim missionary. The five-part comedy series Them (1972) starred Booth and Cyril Cusack as two tramps, "Cockney" and "Coatsleeves." Regrettably, neither Vessel nor Them has been preserved in any format.

Determined to forestall any more money problems, Booth invested in a real estate company that rehabbed and sold apartments. For a time it did very well. By 1971 Booth was driving Jaguars and Rolls Royces and living “a push-button lifestyle” with his family in a fifteen-room Tudor mansion set on four acres at Lower Brook End, Buckinghamshire. In addition, Booth teamed up with writer Johnny Speight in a company called Speijim (though, by Booth’s own admission, the company was mostly an excuse to go to pubs).

Crash and Burn

Then, in three months in 1974, Booth’s real estate investments tanked, his financial instruments failed, and Booth lost everything. Show business was still Booth’s primary occupation, and could have offset this loss of income. But Booth's acting career had also fallen on hard times. He later admitted he had done serious damage to his own professional reputation by showing up for work intoxicated or unprepared, in an industry with little tolerance for delays and the actors who cause them. The desirable film offers that Booth had once attracted so effortlessly came no more. He had little choice but to accept a bit part in the dumb sexploitation comedy Percy’s Progress (1974), a small role as a criminal in the John Wayne vehicle Brannigan (1975), and a large part in the dumb sexploitation comedy I’m Not Feeling Myself Tonight (1976).

Booth compensated by stepping up his stage work. In 1974 he renewed his association with the Royal Shakespeare Company, appearing in Measure for Measure, The Tempest, and Afore Night Come. The following year he played James Joyce in Tom Stoppard’s abstractly intellectual historical play Travesties, which ran for eight months in New York City and was voted best play of the 1975-76 season by the New York Drama Critics Circle. However, much as Booth loved the theater, he felt there was no way he could pay off his large debts by acting in plays.

Metamorphosis

There can be no doubt that this period was painful and psychologically difficult for Booth. Depressive by nature, and inclined toward self-doubt to begin with, he had suffered professional and financial setbacks that might have discouraged anyone. Taking stock of himself and his life, he said, he didn’t like what he saw. He should have helped Joan Littlewood more. He should have spent less time in pubs, more time with his kids. He should have worked harder and drunk less. He describes going through a spiritual crisis at this time. The turning point came when an inner voice told Booth, “Why don’t you get up off your backside, stop being a drunk and go out there and create.” It was good advice, and Booth took it. He went on the wagon and rededicated himself to working hard and being creative.

Unable to pay the fees for his kids at prestigious Millfield school, Booth contacted the administration and found himself talking to producer Irving Allen, who happened to be on the Millfield board. As a result of that conversation, Booth got the opportunity to create a screenplay from James Jones’s The Pistol. Booth modestly offered to write the script gratis, but Allen deemed Booth’s screenplay “terrific” and paid him. Though The Pistol was never filmed, the project restored Booth’s confidence and suggested to him a possible avenue for future creative employment.

Welcome to LA

With the British film industry drying up all around him, and his own film career in tatters, Booth took a huge gamble and moved to Los Angeles to start afresh. He went alone, intending to send for his family later, and for the next year he surfed the couches of his friends while seeking opportunities to act or screenwrite. Though the search for work produced nothing, Booth’s wife and children joined him in LA.

Booth was down to his last $25 dollars, utterly fed up with show business, ready to quit and “drive a cab.” Suddenly, in a moment worthy of Dickens, one of his screenplays brought him $23,000 in readies, and within a week Booth was offered a guest-starring role in a TV movie for $20,000.

Booth’s gamble had paid off. He had come to the US in search of economic opportunity and, like so many immigrants before him, he had found it. Though he never gave up his British citizenship, for the next two decades Booth lived with his family in southern California.

In addition to doing lots of rewrite work, Booth wrote dozens of screen adaptations and original screenplays, under various names, including David Greeves, Grieves, and Geeves, as well as James Booth. He won the Irving Berlin Award for best lyricist for an adaptation of Ben Jonson’s Alchemist, called The Al Chemist Show. He also wrote screenplays for, and acted in, the martial arts movie Pray for Death (1985) and two American Ninja films (1986, 1991). Booth also wrote a screen adaptation of King Lear, called King Harry, in which Paul Newman was interested but which was never produced.

Though writing had become his primary occupation, Booth continued to act when opportunities presented themselves. He played the Voice of God in a production of Benjamin Britten's Noye's Fludde (1979). He had small regular roles in two cult TV series, the British sitcom Auf Wiedersehen Pet (1983) and David Lynch's noir-surrealist art-soap Twin Peaks (1990-91), and made guest appearances in Bergerac (1990), Lovejoy (1991), and Minder (1993). In addition, he was cast as a regular (playing a Russian official) in a TV series about terrorism (The Red Phone [ 2001]) that never aired. Returning to the stage in 1994, Booth played the cuckolded New England patriarch Ephraim Cabot in Eugene O'Neill's Desire Under the Elms.

Home Sweet Home

Toward the end of his life, Booth moved back to England with his wife because Paula was homesick. The Booths settled in Benfleet, Essex, near the Southend-on-Sea area that had been important to James’s childhood. However, three of the four Booth offspring, now grown, stayed behind in the US. James and Paula divided their time between the UK and the US, maintaining close ties with their two daughters, two sons, and five grandchildren.

Booth remained professionally active to the end. His final project was the film Keeping Mum (2005), a charming dark comedy in which he plays “a grumpy old man.” He died peacefully in his own bed on the morning of August 11, 2005, aged 77. His final resting place is in Essex, near Hadleigh Castle, on the Thames Estuary, close to Paula and their home.

Text copyright Diana Blackwell, 2005.